Struggling with loneliness? You’re not alone

Let’s start with the sad and scary part.

Loneliness is not only psychologically painful, it can be deadly. Research has consistently suggested that individuals lacking social connections are likely to die younger.1

To make matters worse, loneliness also appears to be bad for your heart.2 The leading cause of death in Australia? Coronary heart disease.3 Being meaningfully connected looks and feels different for each one of us. I would contend that being lonely, truly disconnected and isolated, feels awful for all of us.

I have experienced loneliness, subjectively. While I cannot attest to a period in my life when I was completely alone, I vividly remember a time when I felt lonely. Disconnected and distrusted. Although I was far from faultless, I completely blamed myself.

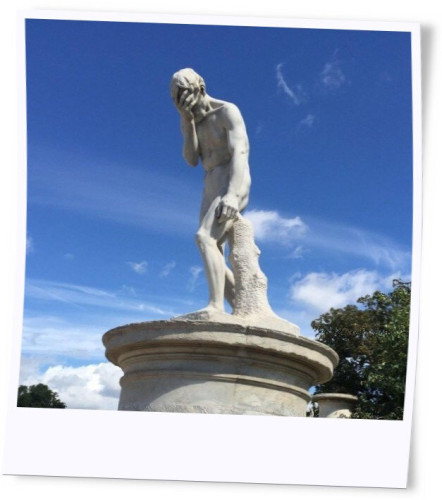

As it turns out, part of this period in my life occurred while I was on vacation. In Paris – my favourite holiday destination – of all places. I was on an early morning jog in the Jardin des Tuileries, and I came across this statue:

It stopped me in my tracks. So much so that I decided to take this photo.

It turns out the statue is of the Biblical character Cain, depicted in that moment after killing his brother. Apart from the appropriate guilt and remorse Cain was feeling in this story, I imagine he had never felt more alone, and that he blamed himself. As the story goes, Cain was to become a restless wanderer. A loner, we might say today. Loneliness has been around as long as humans have been.

It turns out that my experience of loneliness is not that unusual in the present age, either. Loneliness was recognised as a public health issue before the pandemic,4 and in many parts of Australia Covid-19 has exposed and amplified social isolation and loneliness, as well as their impacts on wellbeing and mental health.5

I’ve experienced subjective loneliness. A helpful example might be feeling all alone when you’re at a party. We’ll get to that in a little bit. Objective loneliness, on the other hand, is typically about being literally isolated, or cut off. Objective loneliness is largely a problem that can be prevented and addressed proactively.

A few examples:

- The Community Visitors Scheme: a Commonwealth Government initiative for people receiving Home Care Packages or government-subsidised residential aged care which aims to develop social connections and friendships by matching volunteers with older people who are isolated

- Social Prescribing: the research is compelling – loneliness adversely impacts our physical health. Social prescribing shifts the focus of our interactions with GPs to our needs and wider social networks. This can address underlying issues, such as loneliness, and lead to better outcomes long-term6

- Psychological therapy: therapy can address issues that make it challenging for people to establish relationships, such as anxiety associated with social situations.7

When working with clients who are experiencing a host of mental health issues, which loneliness cuts across, I find myself emphasising two things in therapy: self-compassion and mindfulness. The research suggests that these things help.8

According to the well-known self-compassion researcher, Dr Kristin Neff, the term is sometimes conflated with “self-pity, self-serving, self-indulgent, self-centered, just plain selfish... we still seem to believe that if we aren’t blaming and punishing ourselves for something, we risk moral complacency, runaway egotism, and the sin of false pride.”9

Self-compassion, at its most simplest, means treating yourself the same way you’d treat a friend who is suffering – with love, empathy, and care. How does that relate to loneliness? We can gently remind ourselves that we’re human, that humans have always struggled with loneliness, and even psychologists – supposed experts in human interactions and behaviours – can suffer with it too. Self-compassion means we give ourselves a break.

What about mindfulness? How does mindfulness, which suggests that we become aware of and even accept psychological and emotional pain, help address loneliness?

Well, we hurt where we care.

And most of us, if not all of us, care about connection. Acknowledging the pain of loneliness reminds us of what is most important, and in being reminded, we can find clarity and purpose. Mindfulness is also about being present, and when we remain in the present moment, we might even connect to a sense of something bigger than ourselves.

That certainly helped me find hope when I felt alone and dejected, and I hope it might help you too.

En Masse offers a number of online and face-to-face mindfulness workshops incorporating the practical component of guided mindfulness exercises to promote wellbeing and work performance outcomes. Talk to us today about a program targeted to the needs of your team.

Reference

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspectives on psychological science: A journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10, 227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352

- Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. BMJ Heart 2016;102:1009-1016.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2021. Deaths in Australia. Cat. no. PHE 229. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 25 June 2021, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/life-expectancy-death/deaths-in-australia

- Lim M. (2018). Australian loneliness report: A survey exploring the loneliness levels of Australians and the impact of their health and wellbeing. Australian Psychological Society and Swinburne University. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.3/446718

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). The use of mental health services, psychological distress, loneliness, suicide, ambulance attendances and COVID-19. https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/covid-19

- Brandling, J., House, W. (2009). Social prescribing in general practice: adding meaning to medicine. British Journal of General Practice, 59, 454-456. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X421085

- Griffin, J. (2010). The Lonely society? Mental Health Foundation. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/the_lonely_society_report.pdf

- Teoh SL, Letchumanan V, Lee LH. (2021). Can Mindfulness Help to Alleviate Loneliness? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 633319. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633319

- Neff K. (2015, Sep 30). The Five Myths of Self-Compassion. Greater Good Science Center: University of California, Berkeley https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/the_five_myths_of_self_compassion